Matthew L. Harris is the author of numerous books and articles, including Second-Class Saints: Black Mormons and the Struggle for Racial Equality (Oxford University Press, 2024), Watchman on the Tower: Ezra Taft Benson and the Making of the Mormon Right (Univ. of Utah Press, 2020), The LDS Gospel Topics Series: A Scholarly Engagement (Signature Books, Sept 2020), The Mormon Church and Blacks: A Documentary History (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2015), Thunder on the Right: Ezra Taft Benson in Mormonism and Politics (Univ. of Illinois Press, 2019), Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West (Univ. of Oklahoma Press 2012), The Founding Fathers and the Debate over Religion in Revolutionary America: A History in Documents (Oxford University Press, 2011)

He is currently at work on two book-length manuscripts: J. Reuben Clark and the Making of Modern Mormonism (Univ. of Illinois Press); and Hugh B. Brown: Mormonism’s Progressive Apostle (Signature Books).

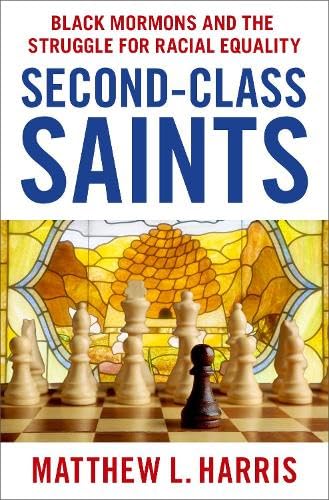

An in-depth account–grounded in new archival discoveries–of the most consequential development in Mormon history since the end of polygamy

On June 9, 1978, the phones at the headquarters of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) were ringing nonstop. Word began to spread that a momentous change in church policy had been announced and everyone wanted to know: was it true? The answer would have profound implications for the church and American society more broadly.

On that historic day, LDS church president Spencer W. Kimball announced a revelation lifting the church’s 126-year-old ban barring Black people from the priesthood and Mormon temples. It was the most significant change in LDS doctrine since the end of polygamy almost 100 years earlier.

Drawing on never-before-seen private papers of LDS apostles and church presidents, including Spencer W. Kimball, Matthew L. Harris probes the plot twists and turns, the near-misses and paths not taken, of this incredible story. While the notion that Kimball received a revelation might imply a sudden command from God, Harris shows that a variety of factors motivated Kimball and other church leaders to reconsider the ban, including the civil rights movement, which placed LDS racial policies and practices under a glaring spotlight, perceptions of racism that dogged the church and its leaders, and Kimball’s own growing sense that the ban was morally wrong.

Harris also shows that the lifting of the ban was hardly a panacea. The church’s failure to confront and condemn its racial theology in the decades after the 1978 revelation stifled their efforts to reach Black communities and made Black members the target of racism in LDS meetinghouses. Vigilant members pestered church leaders to repudiate their anti-Black theology, forcing them to live up to the creed in Mormon scripture that “all are alike unto God.” Deeply informed, engagingly written, and grounded in deep archival research, Harris provides a compelling and detailed account of how Mormon leaders lifted the priesthood and temple ban, then came to reckon with the church’s controversial racial heritage.

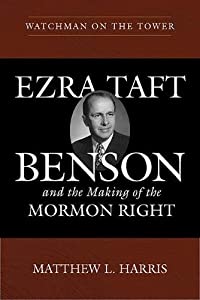

Ezra Taft Benson is perhaps the most controversial apostle-president in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For nearly fifty years he delivered impassioned sermons in Utah and elsewhere, mixing religion with ultraconservative right-wing political views and conspiracy theories. His teachings inspired Mormon extremists to stockpile weapons, predict the end of the world, and commit acts of violence against their government. The First Presidency rebuked him, his fellow apostles wanted him disciplined, and grassroots Mormons called for his removal from the Quorum of the Twelve. Yet Benson was beloved by millions of Latter-day Saints, who praised him for his stances against communism, socialism, and the welfare state, and admired his service as secretary of agriculture under President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Using previously restricted documents from archives across the United States, Matthew L. Harris breaks new ground as the first to evaluate why Benson embraced a radical form of conservatism, and how under his leadership Mormons became the most reliable supporters of the Republican Party of any religious group in America.

This anthology provides a scholarly, in-depth analysis of the thirteen Gospel Topics essays issued by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from December 2013 to October 2015. The contributors reflect a variety of faith traditions, including the LDS Church, Community of Christ, Catholic, and Evangelical Christian. Each contributor is an experienced, thoughtful scholar, many having written widely on religious thought in general and Mormon history in particular. The writers probe the strengths and weaknesses of each of the Gospel Topics essays, providing a forthright discussion on the relevant issues in LDS history and doctrine. The editors hope that these analyses will spark a healthy discussion about the Gospel Topics essays, as well as stimulate further discussion in the field of Mormon Studies.

Ezra Taft Benson’s ultra-conservative vision made him one of the most polarizing leaders in the history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His willingness to mix religion with extreme right-wing politics troubled many. Yet his fierce defense of the traditional family, unabashed love of country, and deep knowledge of the faith endeared him to millions. In Thunder from the Right, a group of veteran Mormon scholars probe aspects of Benson’s extraordinary life. Topics include: how Benson’s views influenced his actions as Secretary of Agriculture in the Eisenhower Administration; his dedication to the conservative movement, from alliances with Barry Goldwater and the John Birch Society to his condemnation of the civil rights movement as a communist front; how his concept of the principal of free agency became central to Mormon theology; his advocacy of traditional gender roles as a counterbalance to liberalism; and the events and implications of Benson’s term as Church president. Contributors: Gary James Bergera, Matthew Bowman, Newell G. Bringhurst, Brian Q. Cannon, Robert A. Goldberg, Matthew L. Harris, J. B. Haws, and Andrea G. Radke-Moss.

The year 1978 marked a watershed year in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as it lifted a 126-year ban on ordaining black males for the priesthood. This departure from past practice focused new attention on Brigham Young’s decision to abandon Joseph Smith’s more inclusive original teachings. The Mormon Church and Blacks presents thirty official or authoritative Church statements on the status of African Americans in the Mormon Church. Matthew L. Harris and Newell G. Bringhurst comment on the individual documents, analyzing how they reflected uniquely Mormon characteristics and contextualizing each within the larger scope of the history of race and religion in the United States. Their analyses consider how lifting the ban shifted the status of African Americans within Mormonism, including the fact that African Americans, once denied access to certain temple rituals considered essential for Mormon salvation, could finally be considered full-fledged Latter-day Saints in both this world and the next. Throughout, Harris and Bringhurst offer an informed view of behind-the-scenes Church politicking before and after the ban. The result is an essential resource for experts and laymen alike on a much-misunderstood aspect of Mormon history and belief.

In life and in death, fame and glory eluded Zebulon Montgomery Pike (1779–1813). The ambitious young military officer and explorer, best known for a mountain peak that he neither scaled nor named, was destined to live in the shadows of more famous contemporaries—explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. This collection of thought-provoking essays rescues Pike from his undeserved obscurity. It does so by providing a nuanced assessment of Pike and his actions within the larger context of American imperial ambition in the time of Jefferson.

Pike’s accomplishments as an explorer and mapmaker and as a soldier during the War of 1812 has been tainted by his alleged connection to Aaron Burr’s conspiracy to separate the trans-Appalachian region from the United States. For two hundred years historians have debated whether Pike was an explorer or a spy, whether he knew about the Burr Conspiracy or was just a loyal foot soldier. This book moves beyond that controversy to offer new scholarly perspectives on Pike’s career.

The essayists—all prominent historians of the American West—examine Pike’s expeditions and writings, which provided an image of the Southwest that would shape American culture for decades. John Logan Allen explores Pike’s contributions to science and cartography; James P. Ronda and Leo E. Oliva address his relationships with Native peoples and Spanish officials; Jay H. Buckley chronicles Pike’s life and compares Pike to other Jeffersonian explorers; Jared Orsi discusses the impact of his expeditions on the environment; and William E. Foley examines his role in Burr’s conspiracy. Together the essays assess Pike’s accomplishments and shortcomings as an explorer, soldier, empire builder, and family man.

Pike’s 1810 journals and maps gave Americans an important glimpse of the headwaters of the Mississippi and the southwestern borderlands, and his account of the opportunities for trade between the Mississippi Valley and New Mexico offered a blueprint for the Santa Fe Trail. This volume is the first in more than a generation to offer new scholarly perspectives on the career of an overlooked figure in the opening of the American West.

Whether America was founded as a Christian nation or as a secular republic is one of the most fiercely debated questions in American history. Historians Matthew Harris and Thomas Kidd offer an authoritative examination of the essential documents needed to understand this debate. The texts included in this volume – writings and speeches from both well-known and obscure early American thinkers – show that religion played a prominent yet fractious role in the era of the American Revolution.

In their personal beliefs, the Founders ranged from profound skeptics like Thomas Paine to traditional Christians like Patrick Henry. Nevertheless, most of the Founding Fathers rallied around certain crucial religious principles, including the idea that people were “created” equal, the belief that religious freedom required the disestablishment of state-backed denominations, the necessity of virtue in a republic, and the role of Providence in guiding the affairs of nations. Harris and Kidd show that through the struggles of war and the framing of the Constitution, Americans sought to reconcile their dedication to religious vitality with their commitment to religious freedom.